Enniskillen - The Guerilla Campaign

Most Ulster folk can tell the inquirer about the Boyne and

the Siege of Derry, but fewer are able to relate the events

which took place at Enniskillen and Aughrim. The sterling

qualities of the Derry men were manifested in their fortitude

while passing through severe trials, and in their patient

endurance of conditions involving hunger and suffering and

death.

The

virtues of the Enniskilleners were cast in a different mould

and displayed in different forms. The basis of the force was

composed of inhabitants of the town who took up arms for self

defence. They were joined by a large number of the yeomen

of County Fermanagh. Subsequently reinforcements came from

Cavan, Monaghan, Donegal, Leitrim and Sligo; but the force

was essentially local and exclusively Protestant, and all

were known by the general name of the Enniskillen Men. The

virtues of the Enniskilleners were cast in a different mould

and displayed in different forms. The basis of the force was

composed of inhabitants of the town who took up arms for self

defence. They were joined by a large number of the yeomen

of County Fermanagh. Subsequently reinforcements came from

Cavan, Monaghan, Donegal, Leitrim and Sligo; but the force

was essentially local and exclusively Protestant, and all

were known by the general name of the Enniskillen Men.

A copy of the anonymous letter to Lord Mount-Alexander, announcing

the intended massacre of the Protestants, reached them on

the day Derry closed its gates against the Redshanks (7th

December 1688). On the 11th December, a letter was received

from the Government authorities in Dublin, directing them

to make arrangements for having two companies of infantry

quartered in their town. It was an unusual thing to have a

garrison planted among them, and the probability, as they

believed, was, that the day for cutting their throats was

only postponed until everything was ready.

While the town was in a state of uncertainty as to what ought

to be done, three men, William Browning, Robert Clarke, and

William MacCarmick, to whom were soon afterwards added James

Ewart and Allen Cathcart, came together. They resolved to

refuse admittance to the soldiers, whatever consequences might

ensue. The Prince of Orange, as they knew, had landed in England

some five weeks before. Civil war was imminent in Ireland.

North and South most likely would be pitted against each other;

and it appeared to them that, by refusing to admit the troops,

they might be able, not only to protect themselves, but to

hold the most important town between Connaught and Ulster,

it was nevertheless a mad resolve, in the face of the facts.

Arrayed against them was the whole power of the Irish Government,

and that all the means of resistance Enniskillen had was ten

pounds of powder, twenty firelocks, and eighty men. The five

men, however, did resolve, sent notice of their determination

to the surrounding country, craved its assistance, set carpenters

at work on the drawbridge, in connection with the stone bridge

latterly erected at the east end of the town, and, like men

in earnest, took every step that they could think of to increase

their power of resistance.

On the 16th, the news came that the two foot companies sent

by Tyrconnell, had reach Lismella, only four miles from the

town. The townsmen, took up arms, and put themselves in array.

Notwithstanding all the help sent them by the country, their

whole strength did not exceed two hundred foot, and one hundred

and fifty horse, ill-armed, and with no military training

or experience. They left town with the intention of persuading,

if possible, the soldiers to return, but prepared, if necessary,

to resist their entrance. No sooner did the soldiers come

in view of the Enniskilleners than, without waiting for their

approach, they turned and fled.

During the remaining part of 1688 little was done at Enniskillen

except to break the ice around the town, which during that

winter was so thick as to permit men on horseback to cross

Lough Erne in safety and which to some extent imperiled the

safety of the little garrison that was protected by no walls

save walls of water.

Early in 1689 Hamilton, now the Governor of Enniskillen,

formed his men into regiments and fortified the town as best

he could, laying in stores of food, forage and ammunition.

The Enniskilleners resolved "To stand upon our guard

and by the blessing of God, rather to meet our danger than

to expect it."

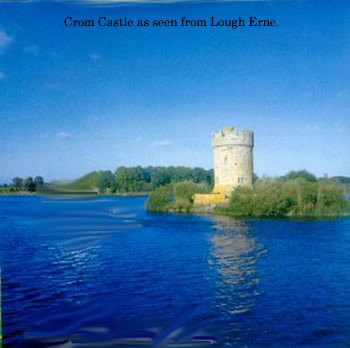

Crom Castle an outpost of Enniskillen was besieged

by a force of Jacobites under Lord Galmoy. Crom Castle was

under the command of Colonel Crichton. The position of the

castle made it difficult to defend. One saving grace was the

marshy ground, which meant that no heavy siege guns could

be brought near enough to bombard the stronghold. Colonel

Crighton sent a dispatch for help to Governor Hamilton requesting

immediate action so that this outpost could be saved. In the

night Hamilton sent a detachment of 200 of his best armed

men, some by land, some by water, hoping they might enter

Crom Castle under cover of darkness. The reinforcement having

joined those within the walls, they sallied out together,

drove the besiegers from their trenches, and killed about

forty of them. Galmoy at once raised the siege, and retreated.

Flushed with their success at Crom Castle, Hamilton and Lloyd

decided to act as they had resolved to, and went on the offensive.

Intelligence reached Enniskillen that the Irish had placed

a garrison at Trillick, nine miles distant. On the 24th April,

Colonel Lloyd marched against that place. Early intimation,

however, of his approach had been received at Trillick, and

the post was evacuated. Lloyd followed in rapid pursuit, and

after a disorderly retreat of six hours the party dispersed

and took to the bogs. Their baggage and a large number of

cattle were captured. The Castle of Augher, eighteen miles

distant, had been recently occupied by James' party. Early

on the morning of the 28th of April, Lloyd tried to surprise

it, but again the garrison abandoned the post, taking away

with them everything portable. Lloyd, having swept part of

Monaghan and Cavan, returned on the 2nd of May to Enniskillen

with great abundance of sheep, cattle and provisions.

On the 4th May, Ffolliott, the Governor of Ballyshannon,

sent a despatch to Enniskillen, informing Hamilton that a

large body of Jacobites had advanced from Connaught to besiege

his post and begged to be speedily relieved. On the 7th may,

Lloyd proceeded towards Ballyshannon. The besiegers, leaving

a small force to watch the town, advanced three miles to Beleek

to met him. Here they drew up, in a very advantageous position,

their flanks protected on the one side by the lough, and on

the other by a bog of great extent. A narrow causeway formed

the only apparent approach. This they entrenched, and destroyed

the bridge. At a critical moment, a countryman offered to

guide them through the bog. The horse under Captain Acheson

passed in safety, and moved towards their left to turn the

enemy's right flank, and thus cut off their retreat to the

mountains. Before the opposing armies came within shot, the

Irish foot broke and fled to the hills. Their horse, drawn

up to the left of their foot, and between them and the lake,

stood their ground, until charged by the Enniskillen horse,

when, without awaiting the shock, they turned and fled. They

were followed for a great distance, and night alone put an

end to the pursuit. In this encounter the Jacobites lost 190

killed and 60 captured. The victors plundered the enemy camp

and brought all arms, ammunition and two small cannon back

to their island home without losing a man.

When at the end of May there were reports that the Jacobites

had garrisoned Redhill and Ballinacarrig in County Cavan,

Lloyd marched out with 1,600 men to confront the enemy. They

proceeded to drive the enemy out of their strongholds without

firing a shot, using the ploy that they were the vanguard

of a much larger force. They then marched into County Meath

and captured 3,000  head

of cattle, 2,000 sheep and 500 horses and drove them back

to Enniskillen. This sortie of Lloyd's stopped 25 miles from

Dublin and caused a great panic in that city. head

of cattle, 2,000 sheep and 500 horses and drove them back

to Enniskillen. This sortie of Lloyd's stopped 25 miles from

Dublin and caused a great panic in that city.

While Lloyd's raid was taking place, Hamilton captured the

horses belonging to the garrison at Omagh. Cornagrade, which

lies about two miles north-east of Enniskillen was the only

place where Enniskilleners were to taste defeat in the campaign.

The Duke of Berwick roved the country with a flying column

of horse, and his force approached Enniskillen while Lloyd

was meeting Major General Kirke at Lough Swilly to request

help for the newly raised regiments at Enniskillen. Hamilton

sent out insufficent troops to fight and Berwick's men gained

a victory. However, Berwick did not follow up his success.

On the night of the 28th July, a few hours after Colonel

William Wolseley, Lieutenant-Colonel William Berry, Major

Stone, Colonel James Winn, Colonel Tiffan, and other offices

sent by Major-General Kirke, had arrived in Enniskillen, an

express came from Colonel Crighton announcing that Lieutenant-Colonel

MacCarthy (created Lord Mountcashel) had formed a camp at

Crom, with the intention of besieging the castle. Colonel

Wolseley replied that he would provide relief; and he called

in the forces at Ballyshannon, left there by Lloyd, who had

returned to Enniskillen. The Colonel sent Berry to place a

garrison in Lisnaskea; but the castle was in ruins, and he

camped out that night. Next morning he marched his men two

miles nearer the enemy, and, having met a party of Jacobite

soldiers at Conagh, a sharp conflict ensued. The enemy was

completely beaten and pursued for three miles. Berry retired

to the Moat at Lisnaskea, and was joined there by Wolseley

and the rest of the Enniskillen forces.

In the afternoon of the 30th July, Wolseley held a council

of war, and explained to the officers that whatever they resolved

to do should be done quickly, his men having made such haste

to relieve their comrades that they had not brought food with

them. Accordingly, early next morning Wolseley formed his

forces, which numbered two thousand, into three battalions,

heading the main body himself. Lloyd commanded the right and

Tiffan the left wing and marched towards Newtownbutler. Lord

Mountcashel, retreated from Crom to a place between Newtownbutler

and Wattlebridge, where he took up a good position. The foot

occupied a bog, with only one narrow pass, protected by two

cannon. This put the Enniskillen Men at a disadvantage and

the foot regiments of Lloyd and Tiffin were forced to march

through the bog on either side of the path. Presently a man

belonging to Lord Kingston's corps seized a hatchet and killed

seven or eight of those who were guarding the cannon. Wolseley's

horse immediately charged through the Pass; and the Jacobite

horse fled towards Wattlebridge, but were hemmed in by the

Enniskillen horse. The Jacobite foot betook themselves to

the bogs, throwing away their arms, and were pursued all that

night by Enniskilleners, who kept beating the bushes for the

fugitives. Of the Jacobites, 2,000 were killed, 500 jumped

into Lough Erne, and every man except one was drowned. 500

were carried prisoners to Enniskillen, including General Lord

Mountcashel, and a great many officers. Of the 3,600 men who

marched out of Dublin with Mountcashel at their head only

600 returned to the city. The joy of this victory was made

all the sweet when the news of the relief of Derry reached

Enniskillen.

The north was held for King Wiliam and the fate of the Williamite

campaign was determined.

Back to History Home Page

Back to The Williamite

Wars Home Page

|