The Siege of Londonderry

Outside of the Battle of the Boyne the event which arguably

had the greatest influence on the struggle between William

and James for the soul of Ireland was the Siege of Londonderry.

The refusal of the people of Londonderry to refuse admission

to the Jacobite forces was not initially out of enthusiasm

for the cause of William.

The real motive underlying that decision was the instinct

of self-preservation. The citizens believed that a massacre

of the British was imminent with the memory of horrific happenings

of 1641 still vivid.

The fear and alarm was heightened by an anonymous letter

(The Comber Letter) dated December 3, 1688 received by the

Earl of Mount-Alexander warning him of a plan to massacre

the Protestants of the North on December 9.

The defences of Londonderry seemed contemptible. Its position

was far from impregnable, the stock of provisions was small

and the population had swollen to eight times its usual number

by refugees from the surrounding countryside.

Colonel Lundy, now the Governor, had no thought of a successful

defence, for the task seemed impossible. He did not hide his

feelings from the people.

When the news reached William that the city had declared

for him he determined to send it much-needed help. Lt. Col.

John Cunningham and Colonel Solomon Richards were ordered

to proceed to Londonderry with two regiments of soldiers and

reached the Foyle on April 14, where they anchored in the

bay.

Cunningham, Richards, and their officers went ashore and

consulted with Lundy. He dissuaded them from landing with

their soldiers when he told them the position was so impossible

that reinforcements could only make matters worse. He advised

them to go back to England with ships and men, something he

intended to do if he got the chance.

Lundy in his meeting with Cunningham had ensured that only

those officers of the garrison who thought as he did were

present. Others who felt differently were not invited or were

prevented from attending. But one soldier uttered what those

others believed, "To give up Londonderry is to give up

Ireland."

When the rumour spread of what Lundy and Cunningham had agreed

soldiers and citizens expressed their anger, and many army

officers declared that they no longer considered themselves

to be bound to obey the orders of the Governor. After dusk

on April 17, Lundy's friends secretly fled the city one by

one.

Next day at a special council meeting angry citizens abused

Lundy for his treachery in sending the troops away that William

had sent to defend them. While the meeting was in progress

a sentry on the walls cried out that the vanguard of the enemy

was in sight. When Lundy ordered that there was to be no firing

of guns at them, Major Henry Baker and Captain Adam Murray

countermanded it and called the people to arms. They were

supported by the Rev. George Walker, Rector of Donaghmore

in Co. Tyrone, who had taken refuge with his parishioners

in the city.

All the able-bodied answered the call and the guns were manned.

When James' Redshanks, under Alexander MacDonnell, Earl of

Antrim, were only 60 yards from the gates of the city they

were closed by the 13 apprentices. Expecting the quiet surrender

as promised by Lundy after the Cunningham meeting, the Jacobites

were greeted with loud cries of "No Surrender",

and gunfire.

Lundy had hidden in his house and from there made his escape

over the city wall. When he arrived in England he was imprisoned

in the Tower of London and he, Cunningham and Richards, were

summoned to appear before a parliamentary Commission. Richards

was exonerated, and Lundy was ordered to be returned to Londonderry

to stand trial for treason but this never happened. The conduct

of Cunningham and Richards had so incensed William that he

had dismissed them by newsletter on April 30.

Without the Governor's leadership or a proper administrative

body the people were determined to withstand the siege at

whatever cost. Adam Murray could have been Governor but he

refused. At a meeting of 15 of the principal officers, Murray

being present, Major Baker was chosen. When he complained

that the military and administrative duties were too much

for one man he was allowed to name an assistant. He chose

the Rev. George Walker as Joint-Governor.

Eight regiments were constituted and each man was given his

orders. In just 24 hours the defence of Londonderry, with

the personnel and material available, was complete. When all

had left the city who wanted to go, and these included the

old, the very young and the sick, 20,000 remained within the

walls; 7,020 men able to fight and 341 officers.

On April 19, a Jacobite trumpeter came to the southern gate

of the city to ask if Governor Lundy's promise of an easy

surrender would be kept. He had to take back the message that

the city would be defended against attack for the defenders

had only contempt for their former Governor who had made that

treasonable promise.

Next day, Lord Strabane, a high-ranking Jacobite officer,

was sent to offer terms to the city. It was an ultimatum,

too, which would not be carried out if the citizens submitted

to James, "their loyal sovereign". They would be

pardoned and Adam Murray, who received the message, would

be commissioned a colonel in the army and receive a gift of

£1,000.

Murray's reply to the offer was: "The men of Londonderry

have done nothing that requires a pardon, and own no sovereign

but King William and Queen Mary".

When the encounter was reported to James he returned to Dublin,

and left the Siege in the hands of General Maumont with Richard

Hamilton second in command.

The Siege began on April 20 with a battering of the city.

It was soon on fire in several places and many were crushed

as their houses fell on them when the cannons found their

targets. At first the people were shattered by new and horrifying

experiences, but in the way of human kind they quickly adapted

to their difficult and dangerous situation. Their spirit was

so good that on April 21, Murray led an attack on the besiegers.

A bloody battle ensued and Maumont at the head of a cavalry

unit making for the scene was struck on the head by Murray's

musket ball and killed.

Because of the obvious determination of the garrison to hold

the city the besiegers, after suffering many casualties, decided

to starve the city into surrender.

An expedition was sent from Liverpool under the command of

Liet-General Percy Kirke for the relief of Londonderry. Kirke's

troops sailed on May 22, but storms at sea forced a long stop,

till June 13, at the Isle of Man, then the ships sheltered

off Rathlin Island reaching the Foyle on June 14.

In the meantime the Londonderry people were defending themselves

with stubborn courage against a numerically stronger and more

experienced military force.

Distress had become acute. By June 8 horseflesh was about

the only meat to be purchased and it was in very short supply.

Tallow was a substitute food and even that was doled out parsimoniously.

When on June 14 the sails of Kirke's ships could be seen

by the sentinels on the roof of the Cathedral hope returned.

But hope was turned to despair when signals sent between the

city and the ships were misread by both. To break the deadlock

a messanger from the fleet managed to elude the Irish guards

by diving under the boom to tell the garrison that Kirke had

arrived with his troops, arms, ammunition, and provisions

to relieve the city. But the joy of the message was followed

by weeks of misery, for Kirke thought it imprudent to attack

the besiegers, and he stayed inactive, at the entrance of

Lough Foyle, for several weeks.

Famine was rampant in the city and pestilence had followed

in the wake of the horrible hunger. Fifteen officers died

of fever in one day and Governor Baker died days later. He

was succeeded quickly by Colonel John Michelburne.

When Dublin Castle heard of Kirke's appearance at Lough Foyle

it was decided that Richard Hamilton who had succeeded Maumont

was not able enough for the command. Conrad de Rosen, Marshal-General

of all His Majesty's Forces, a title conferred on him by King

James on his leaving Dublin, was appointed to take control

of the Siege at Londonderry. Rosen was regarded as a great

soldier. He had been sent by Louis XIV to command the French

in James' forces in 1689.

He arrived among the besiegers on June 19 quickly to be made

aware that not even a Marshal of France could defeat what

he thoughtlessly described as a mob of country gentlemen,

farmers and shopkeepers protected only by a wall that no engineer

would describe as impregnable.

Rosen soon found how stubborn Protestants could be.

The horrific story of the lengths to which the citizens went

just to stay alive and the physical pain and mental anguish

they endured is an example of what people will suffer for

a cause in which they believe fervently.

Kirke's inactivity angered William and the Duke of Schomberg.

About July 13, Kirke received orders from Schomberg, as Commander-in-Chief

of the English forces in Ireland, to relieve Londonderry at

once.

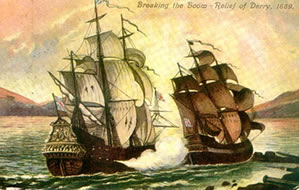

The

Mountjoy, a merchant ship, whose Master was a Londonderry

man, Micaiah Browning, had a large cargo of provisions. As

his ship had been part of the convoy he had angrily attacked

Kirke and the army for their inactivity. Now he volunteered

to take the Mountjoy through to bring succour to his fellow

citizens. He was joined by Andrew Douglas, from Coleraine,

the Master of the Pheonix, which carried a large cargo of

meal from Scotland. The Dartmouth, a frigate of 36 guns, under

Commander John Leake, later to become a famous admiral, was

ordered to accompany them to provide protection. The

Mountjoy, a merchant ship, whose Master was a Londonderry

man, Micaiah Browning, had a large cargo of provisions. As

his ship had been part of the convoy he had angrily attacked

Kirke and the army for their inactivity. Now he volunteered

to take the Mountjoy through to bring succour to his fellow

citizens. He was joined by Andrew Douglas, from Coleraine,

the Master of the Pheonix, which carried a large cargo of

meal from Scotland. The Dartmouth, a frigate of 36 guns, under

Commander John Leake, later to become a famous admiral, was

ordered to accompany them to provide protection.

On July 28 th ships made their perilous journey up the Foyle.

The Mountjoy was in the lead and when it reached the boom

it went straight for it. The boom, intended to prevent ships

from bringing relief to the city, was sited between Charles

Fort and Grange Fort. The Mountjoy broke the boom on July

28, 1689.

There was no more prospect of starving the defenders into

defeat. The failure of the siege was a disaster for James

as it destroyed his hopes of conquering the North and gave

William a firm base in Ulster.

The relieved city was bombarded for three days but on August

1 smoking ruins marked the camping places of the besiegers.

They had retreated up the left bank of the Foyle towards Strabane.

And the most memorable siege in British history had ended

after days of fear, agony and loss. The garrison had been

reduced from 7,000 to 3,000 men.

Lord Macauley, in his history of England, when writing of

the Siege of Londonderry, said: "A people which takes

no pride in the noble achievements of remote ancestors will

never achieve anything worthy to be remembered with pride

by remote descendents."

Back to History Home Page

Back to The Williamite

Wars Home Page

|